„The dimension dissolves every vestige of human individuality“

Helen Waldstein Wilkes was born in Strobnitz/Horni Stropnice. In April 1939, her family fled from Nazi-Germany into Canadian exile. Wilkes earned a doctorate in Romance Studies and taught for over 30 years at schools and universities in Canada and the United States. In retirement, which she spends in Vancouver, she studies her own cultural heritage and its meaning. In this context she wrote a book called "Das Schlimmste war der Judenstern. Das Schicksal meiner Familie". The German journalist Ursula Pidun in conversation with Dr. Helen Waldstein Wilkes.

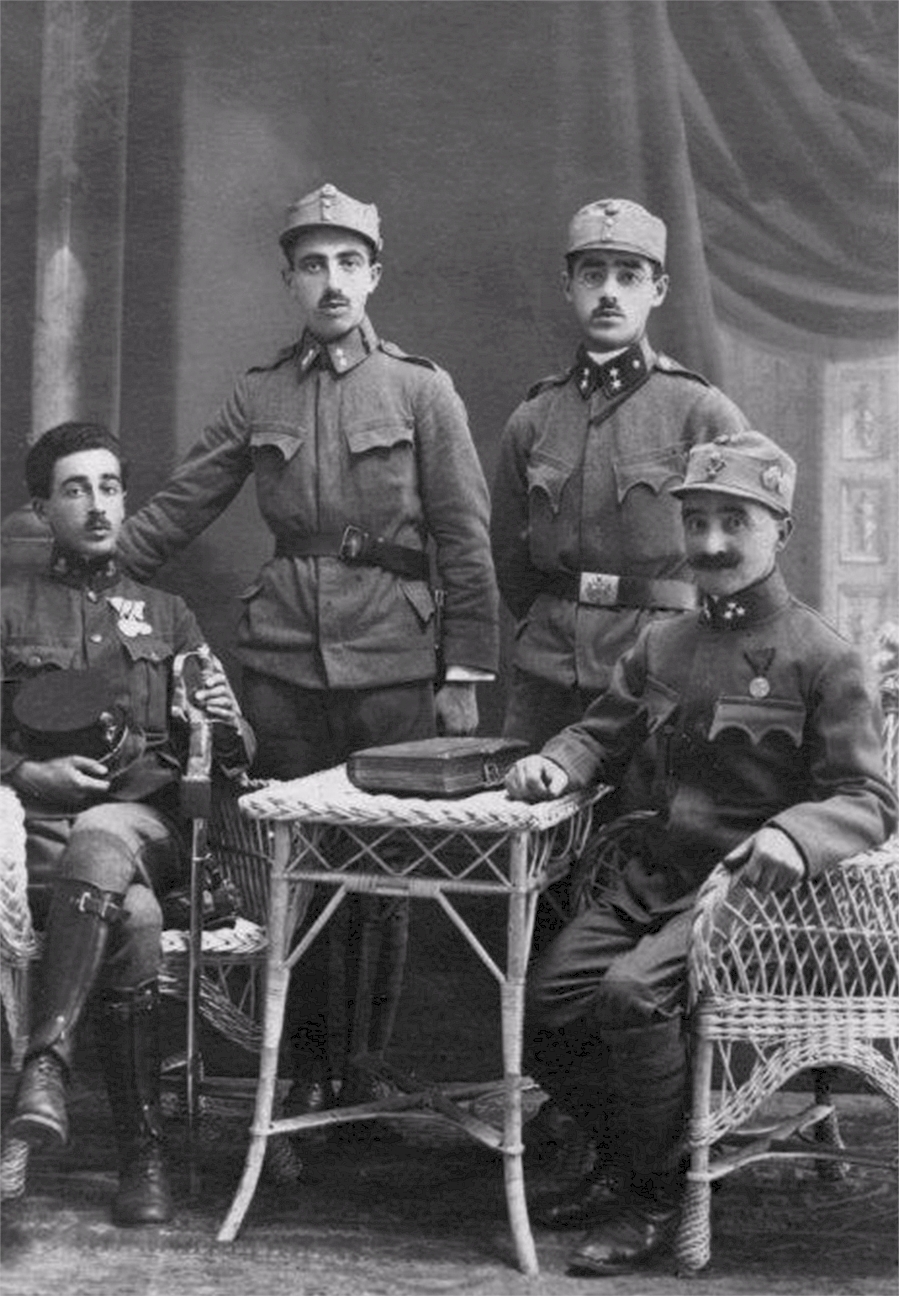

The Waldstein-family in the year 1935 (© H. Wilkes)

„My goal was and is to reach as many readers as possible so that we shall never forget the way things were or how such things might happen again in another way unless people start thinking seriously and critically and learn the difference between truth and propaganda“.

Dr. Wilkes, your family fled into exile in 1939. Do you remember the mood and incredible circumstances of that period?

No, the only memory that I cannot shake is fear. It has been said that the body remembers what the mind has forgotten, and that children absorb fear with their mother’s milk. Whenever and wherever in the world the bombs start to drop, I panic.

Your book has appeared in 2014 under the title The Worst, however, was the Jew Star: the Fate of my Family. What is the underlying idea of your book and did your research result in new findings?

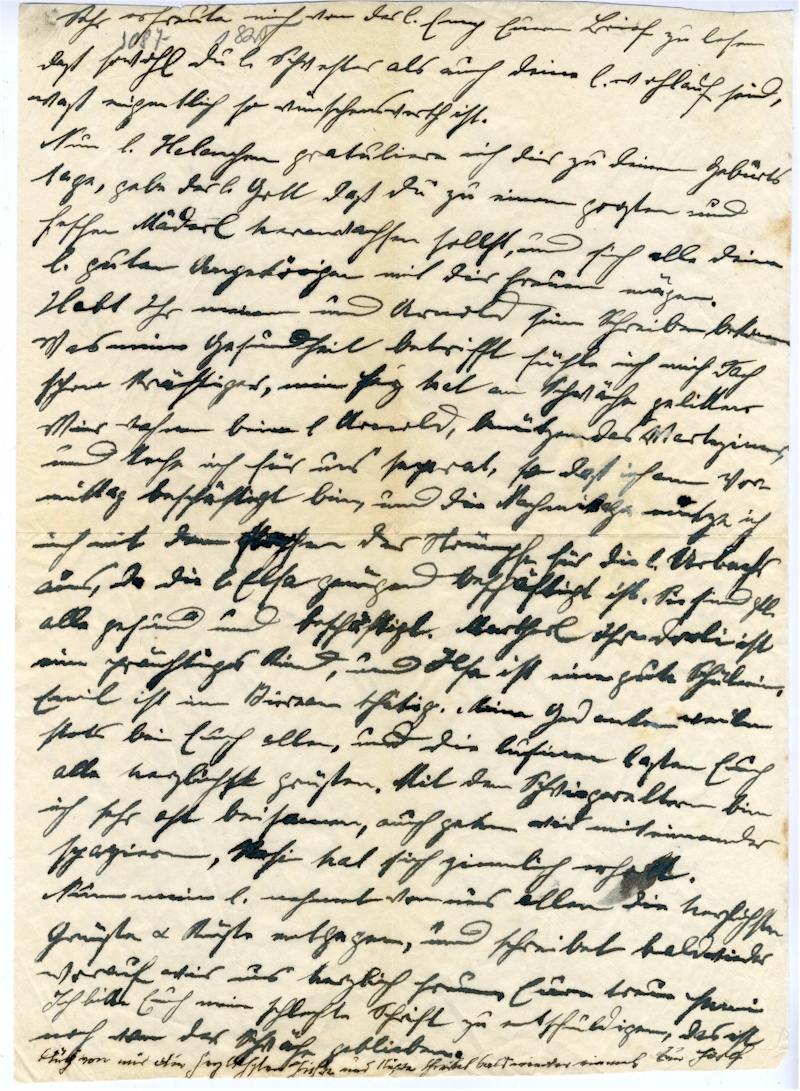

There is a saying: „Know whence you came, that you may benefit from the experience of those upon whose shoulders you stand.“ Until age 60, when I opened a dusty box containing letters from the family who had not survived, I had no idea upon whose shoulders I stood. I grew up on an isolated farm in Canada with parents who refused to speak of the past. I knew very little of how and why we had fled to a land and a life that was so difficult. When I read those letters, it changed everything. All four of my grandparents sprang to life, along with an assortment of beloved uncles and aunts and cousins. I heard their voices, and I knew that I could not simply fold their letters and silence them a second time. They cried out to live and to speak to the world in their own words.

The family fled from Nazi-Germany into Canadian exile. (© H. Wilkes)

And that is how this book began. The more I saw each person who wrote to us in Canada as an individual with a very different reaction to events that were unfolding in Europe, the more important it became to give voice to each individual. Six million is a number, and it erases every vestige of human individuality. I wanted Canadians to see whom they had lost by closing their doors to the immigration of Jews. Eventually, I also wanted Germans to see whom they had lost, these ordinary people who had once been their schoolmates, their friends and neighbours upon whom at the very least, they had turned their backs.

How do you account for the hatred against Jewry that in Germany eventually led to the greatest crime in human history?

(© H. Wilkes)

I am not a historian, and I am not sure how one can determine which is the “greatest” crime in human history. There have been and there continue to be so many horrendous acts ranging from the slaughter of the Armenians to the massacres in Rwanda, from the actions of Stalin and Mao all the way back to Genghis Khan.

The German situation to me personally is appalling because it was deliberate, calculated and carried out by people who were then among the world’s most educated and „civilized.“

I do not believe that Germans are innately evil, and I greatly admire the current generation of Germans who have looked long and hard at the issues that led to the final tragedy.

I think more than any other nation, Germans have learned from the past and taken steps to ensure that the future will not be a repetition of the past. I also agree with authors who point out that it was in part an unfortunate combination of circumstances, and that the degree of anti-Semitism was even greater in other countries.

When people are demoralized, when they are economically deprived, and when they feel that they have no future as was then the case in Germany and is still the situation in parts of the world today, then people will grasp at straws and they will follow any leader who promises them a better life.

The Waldstein-family in the year 1935 (© H. Wilkes)

During the Nazi era, anti-Semitism was largely initiated and legitimized by the state. In your opinion, why did so many citizens jump on the bandwagon of hatred and violence? Could millions of opponents have stopped the Nazis?

Humans love easy answers, and many people are happy when they don’t have to think too much for themselves. Nowadays, neuroscientists have demonstrated that what humans believe is often very different from the actual facts. Instead, there is a strong correlation to influences from childhood to social affiliation and to historical circumstances. „Thanks“ to the early church fathers, medieval Europe had already learned to condemn the Jews as the killers of Christ. Such beliefs do not vanish overnight. Hitler knew how to develop this distrust of the Jews as „Spawn of the Devil“.

As a lifelong educator, what is more difficult for me to understand is how so many highly educated people jumped on the bandwagon. One of my uncles who briefly survived the war describes with utter astonishment the marvels of technology that found their application in Theresienstadt and Auschwitz. Does every scientist have a responsibility to ask how his new findings will be used? A major question for our generation is what and how we should teach students so that past atrocities will never be repeated in any form.

Do you believe the many protestations by Germans of those days that they knew nothing of the extent of Nazi atrocities?

(© H. Wilkes)

No, I do not believe they knew nothing. Too many people were involved in the process, and it was hardly a secret that Hitler was seeking to exterminate the Jews. Some Germans were only involved in knocking on doors at midnight or in herding all Jews like cattle onto the trains. It may be true that they did not ask the destination of the train, but they cannot have escaped knowing that these thousands upon thousands of frightened people were not heading for a happy vacation. Other Germans only drove the train, and did not ask what was in the boxcars, while still others merely directed people to the left of to the right upon arrival at the extermination camps.

At the same time, it may be true that few people were aware of „the full extent of the atrocities because I suspect that few people could have born the truth. The details are simply beyond human imagining. We all like to believe that our group does not commit atrocities and is somehow „better“. We still justify the actions of governments on our behalf, often despite evidence to the contrary. None of us wants to know the full extent of torture deemed necessary in Guantanemo by our American allies. Although that does not make it excusable, it is a human trait to not want to know. For ordinary Germans of the Nazi era, it was easier to imagine their suddenly absent schoolmates and neighbours as having gone to America thant to imagine them being gassed at Auschwitz.

Despite their immeasurable suffering, could your family pardon and can you yourself forgive Germany?

My parents probably did not and could not. „Nie wieder nach Europa“ was their invariable comment after the war when friends began to speak of the pleasures of going „home“ where good food and great music were readily available.

(© H. Wilkes)

For me, the answer is very different. I had grown up in Canada with my own experiences of anti-Semitism, and I had learned that there were good people and bad people in all parts of the world. Once I was old enough to travel, I was repeatedly drawn to Europe and especially to the German-speaking lands where I met more and more people whose kindness and level of understanding astonished me. I am, of course, speaking largely of a new generation, people who themselves were too young to be direct participants, but who have asked the hard questions. And I must stress again and again that in my experience, more than any other nation, Germans have asked these questions and continue to ask them.

With these forgiving words in mind, do you think of certain individuals and encounters in particular?

When I think of a new generation of Germans, I think of those I have met during the research for this book. I picture the young man who took me up the tower in his home town to show me the remains of a concentration camp. Repeatedly he has wrestled with the issue of how his good and caring parents could have acted as they did. I think of strangers who have become my friends, of people who reached out to me with offers of help in translating the book. I think of Germans who welcomed me to their homes as if I were a long-lost cousin, and who have enabled me to put a real face on German kindness. In turn, I have come here to put a real face on being a Jew of German origin, knowing fully that this makes me a Sondervogel, a rare bird in this land where the only Jews are largely recent arrivals from other lands. But my roots are here.

Is the time ripe for significantly more communication, exchange and talk with fellow Jewish citizens and contemporaries?

Absolutely. More and better communication and mutual understanding are crucial. What other way is there to prevent a repetition of the Third Reich and of other historical horrors?

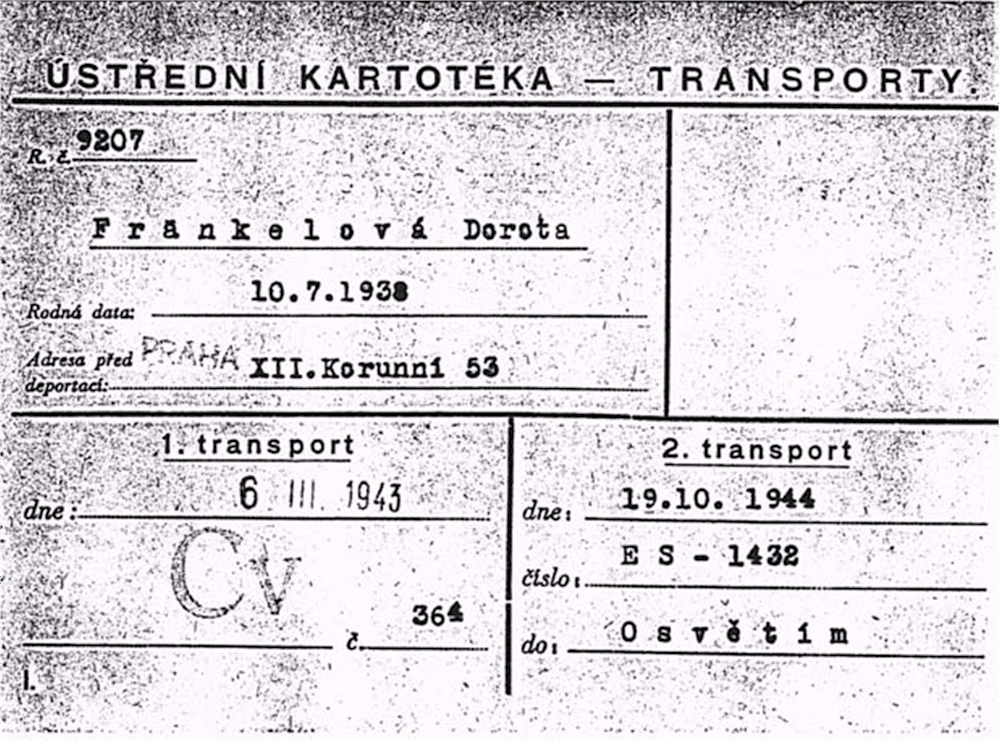

Transport-card from the year 1943 (© H. Wilkes)

What do you wish for in particular with regard to the coexistence of Jewish citizens and contemporaries from other religions and cultures?

I personally think a step in the right direction would be to stop categorizing people according to race or religion or even nationality. I am a Jew, but I no more represent all Jews than you represent all Christians- or all atheists or all members of any group. And certainly, no one of you could claim to speak for all Germans. Jews too have many different opinions on every issue, as do all people.

There are good people and not-so-good people to be found in every family. How much more is that the case in a larger group? There are good people and not so good people to be found in Canada and in Germany and in every other land and in every race and in every culture. No one represents me, and I represent no one else. No one is „typical“, and we must all learn to see each other as individuals rather than as members of a group in whom clever politicians can stir up animosity toward all members of some other group.

References:

„Das Schlimmste aber war der Judenstern. Das Schicksal meiner Familie“

Pingback: Letters from the Lost » Spreezeitung Interview